Beren & Lúthien || Orpheus & Eurydice

At the risk of talking about him too much, let me talk for a minute about J.R.R. Tolkien. As a professor of literature and the father of modern fantasy, it should come as no surprise that Tolkien was deeply familiar with British legends and European mythologies. He drew upon them habitually in his literary career especially when translating Middle English poetry and crafting the world of Middle-earth. As I discussed in “Ex Musica, Magia,” Tolkien often also wove magical music into works, particularly in the various retellings of Beren and Lúthien.1 Perhaps the origin of this fixation on music and magic comes from the Ancient Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Tolkien was certainly aware of the myth, being familiar with the Breton lai Sir Orfeo and having translated it into modern English in 1944.2 (As the title suggests, Sir Orfeo is a Britishized version of the Orphic myth.)

Beren’s and Lúthien’s tales quite closely parallel those of Orpheus and Eurydice. Where it may be easy to do a gendered mapping of Beren to Orpheus and Lúthien to Eurydice, the true Orphic figure of the story is the demigod elf Lúthien, who more closely resembles Orpheus in parentage, heroic deeds, and the futility of her mission. She was the daughter of the Elf-king Thingol and the musically-gifted goddess Melian; she walked into the domain of death where she performed music to quell evil and rescue her love; and she later saved Beren from death even though mortality made his doom inevitable.3 In short, the story of Beren and Lúthien was doubtless informed by that of Orpheus and Eurydice, particularly in archetypal characters and structure and in the use of music as power.

All of that was not really to indulge my Tolkien-loving fancies.4 Rather, I wanted to introduce the prevalence of Orpheus and Eurydice in musical stories. The Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke wrote in his Sonnets for Orpheus, “. . . Ein für alle Male / ists Orpheus, wenn es singt” (“. . . Once and for all, / if there’s singing, it’s Orpheus”).5 In this essay, I want to look at why Orpheus and Eurydice can’t stop popping up wherever there’s music. By delving into the myth itself, doing a little primary research, and discussing other musicologists’ takes on Orphic adaptations, we’ll explore how the Orpheus/Eurydice myth has endured throughout the history of music why music and the myth are such a powerful couple.

Subscribe and share now . . . if you dare! You don’t have to though, but you’re about to embark on a katabasis, so you may as well do that now before you lose yourself in the Underworld.

The Story of Orpheus & Eurydice

Anyone who’s taken a music history survey knows the legend of Orpheus and Eurydice. For the uninitiated, here’s a little synopsis:

Once upon a time, there was a dude named Orpheus. Orpheus was not a god, but he had royal and divine parentage. It’s generally accepted that his dad was King Oeagrus of Thrace and his mom was Calliope, the chief of the Muses and goddess of epic poetry.6 Orpheus learned music from Calliope and became such a great musician that he had no rival save for the gods themselves. In Mythology, Edith Hamilton writes:

There was no limit to his power when he played and sang. No one and nothing could resist him. . . . Everything animate and inanimate followed him. He moved the rocks on the hillside and turned the courses of the rivers.7

Orpheus had been one of the Argonauts, heroes that traveled with Jason aboard his ship the Argo. His lyre and song worked wonders to keep the heroes in high spirits as “their oars would smite the sea together in time to the melody.”8 In one account of the tales of Jason and the Argonauts, Orpheus prevented his companions from falling victim to the seductive songs of Sirens, performing his own tune that drowned out the Sirens’ fatal calls.

When his time with the Argonauts had run its course, Orpheus met the dryad Eurydice and the two were promptly married. Just as promptly, Eurydice was bitten by a viper and died—sad! Orpheus then sang a lament to end all laments and resolved to enter Hades and convince the God of Death to give Eurydice back. He played a lot of music during his descent, assuaging the tempers of all manners of chthonic beings from the three-headed dog Cerberus to the terrifying Furies. At last he met with Hades and Persephone, who after listening to Orpheus sing yet another song, decided oh hell, fine, and permitted Eurydice to leave the Underworld with Orpheus. Just one little caveat, though: Orpheus wasn’t allowed to look back at Eurydice on the way up or else she would be stuck in the Underworld forever. Easy enough.

But Orpheus didn’t trust Hades because he couldn’t feel or hear Eurydice behind him. He held off from peeking behind him until, at the very last moment, Orpheus looked back. He saw Eurydice just long enough to see her vanish back into the Underworld, doomed to a second death. Orpheus tried to rush back after Eurydice, but he was forbidden from reentering the realm of Hades. He wandered around Thrace and played music to cheer himself up, but swore off human contact for the rest of his life. This provoked “the hostility of the Thracian women, who tore him to pieces in a Dionysiac frenzy. His head and lyre, thrown into the river Hebrus, floated to the island of Lesbos.”9 There, the Olympian gods took Orpheus’s lyre and cast it into the sky, forming the constellation Lyra (see Example 1).

What an awesome ending! Some tellings of the legend end a little less macabre. The most well-known alternate ending is an apotheosis of Orpheus in which Apollo, the god of music and sometimes-father of Orpheus, embraces his son and takes him to Olympus to be with the gods.

Orpheus in Music History

The very first work of music to be considered an “opera” was by Jacopo Peri (1561–1633). The name of that opera? Dafne (1598). Dafne was very popular when it premiered, but the manuscript has been mostly lost. That makes Peri’s second opera Euridice (1600)—composed alongside Giulio Caccini (1551–1618)—the earliest complete work in the operatic repertory. Peri and his librettist may have spelled the name wrong and gotten the ending wrong,10 but Euridice cemented Orpheus and Eurydice as the foundation of operatic history. It established the structures of recitative and aria prominently used in opera from the genre’s inception to today (with some Modernist and contemporary experimentation).

Seven years later, the revolutionary composer Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) decided to one-up Peri and Caccini, stepping into the opera world with his own adaptation of Orpheus. Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607) is by-and-large considered the first opera masterwork. A significant difference between Euridice and L’Orfeo is in the narration. Where Peri’s adaptation had La Tragodia (or the Muse of Tragedy) narrate, Monteverdi’s narrator is La Musica. Monteverdi’s La Musica stresses the opera’s inherent connection to music (both in performance and in plot) and its powerful status within the myth. At the beginning of the opera, “Music enters to a ritornello for strings. This ritornello returns at key points in the opera where music and its power come into play.”11 Like a literary motif, the “Music Ritornello” serves as a guidepost that reminds us that “The theme of the opera is the power of music.”12 In the opening of L’Orfeo, Music introduces itself:13

I am Music, who in sweet accents, Can make peaceful every troubled heart, And so with noble anger, and so with love, Can I inflame the coldest minds. Singing with my golden Lyre, I like To charm, now and then, mortal ears, And in such a fasion that I make their souls aspire more For the resounding harmony of the lyre of Heaven. . . . While I vary my songs, now happy, now sad, No small bird shall move among these bushes, Nor on these banks a sounding wave be heard, And every breeze shall stay its wanderings.

Music establishes itself as a powerful and moving force, one that enjoyers of the opera will see Orpheus use repeatedly. The last quatrain is relatively significant, too, as it serves both as a statement of Music’s power over nature and as a metatheatrical gesture, instructing the audience to be silent and attentive as the opera is performed.14

Both Peri/Caccini’s Euridice and Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo are products of the humanist movements of the Renaissance and early Baroque periods.15 During this time, Count Giovanni de’ Bardi gathered a group of scholars in Florence to discuss humanist ideals and their implications for literature, music, science, and art. The Florentine Camerata, as Bardi’s group is often called, desired a return to the artistic practices of Classical antiquity—of Ancient Greece and Rome. As a member of the Camerata, Vincenzo Galilei (the father of Galileo) sought to implant humanist ideals into musical styles:

Through his correspondence with Girolamo Mai and the publication Dialogo della musica antica, et della moderna (1581), Vincenzo Galilei helped to develop the notion that—for music to be truly expressive of its text—it must “return to ancient monody” and follow the natural inflection of speech.16 . . . With [their] claims, Galilei and the Florentine Camerata influenced the perception that music has the power not only to relate to the emotions, but to serve as a vehicle for the emotions. Their findings led to the invention of the stile recitativo, a style composition which imitates the inflections of speech and clearly conveys texts.17

L’Orfeo and Euridice both heavily use recitative as a means to highlight the text being sung and their composers’ adherence to humanist philosophy. Choruses are also used in these operas to provide commentary on the plot, echoing their occasional use in Ancient Greek tragedies as intermediaries between the audience and the tragic characters.18 Orpheus was the perfect vessel to bring the Camerata’s recitative style to the masses. In these early operatic works, the employment of Orpheus was practical; Orpheus was the vessel through which humanist composers sought to reinvent musical styles and to make sophisticated music accessible to any audience.

Across centuries and styles, Orpheus has remained a compelling figure for composers exploring the power and politics of song and the artistic movements of their times. In 1762, Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714–1787) offered his own adaptation entitled Orfeo ed Euridice. In the opera, Gluck sought to heighten the drama of the story by going against prevailing operatic trends and shirking a lot of what he saw as excess in the genre.19 The ballet Orpheus by Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) and George Balanchine (1904–1983) participates in the neoclassical movements of the post-World War era and anticipates a movement toward serialism in Stravinsky’s own compositional style.20 In the folk opera/musical Hadestown (2006), Anaïs Mitchell (1981–) uses the story of Orpheus to discuss modern problems like climate change and workers’ rights, ultimately praising the heroism of endurance in the shadow of disempowerment. Hadestown recognizes “a society that needs the impetus of a celebrated artist [Orpheus] to inspire a great reawakening and make the people care again.” It may go without saying: Orpheus continues to be a creative fountain for composers, offering them familiar and material endlessly adaptable to the movements and urgencies of their time.21

The Emergence of Eurydice

In nearly all of what we’ve seen thus far, Eurydice has been a rather silent character.22 She has a very limited role in the myth, being defined largely by her absence, and has little agency of her own in the vast majority of its retellings. She is typically written as the MacGuffin of the story: the object of Orpheus’s quest rather than an active participant. She’s essentially a “mythological nobody.”23 But not all versions of the myth throw Eurydice into hell and keep her there—metaphorically speaking at least. An early Eurydice-up-lifting setting of the myth appears in the satirical operetta Orphée aux enfers (Orpheus in the Underworld [1858]) by Jacques Offenbach (1819–1880). In the operetta, “Orpheus and Eurydice are bored with each other; the wife particularly loathes her husband’s dreadful violin-playing.”24 So unhappy with Orpheus is Eurydice that when she dies, she euphorically accepts her damnation. No one in the operetta really wants Eurydice to leave the Underworld (Eurydice is enjoying herself, Pluto is in love with her, and Orpheus hates her), so it delights everyone when Zeus causes Orpheus to accidentally look back at Eurydice on their ascent to the surface.25

In her 2003 play Eurydice (adapted as an opera in 2020), Sarah Ruhl goes further by placing Eurydice as the protagonist and emotional center of the story. Shortly after her death in the play, Eurydice is dipped into the river of forgetfulness Lethe. Unknowingly at first, she meets her father in the Underworld who helps her recover her sense of self and memory. Eurydice’s father inevitably partakes of the Lethe and forgets his daughter. After Orpheus’s failed attempt to rescue her, Eurydice succumbs to grief. Eurydice ultimately decides to enter the Lethe once again—to forget her father, her love for Orpheus, and the hell she resides in. In seeking to escape her solitary grief, Eurydice becomes the agent of her own loss of humanity.26

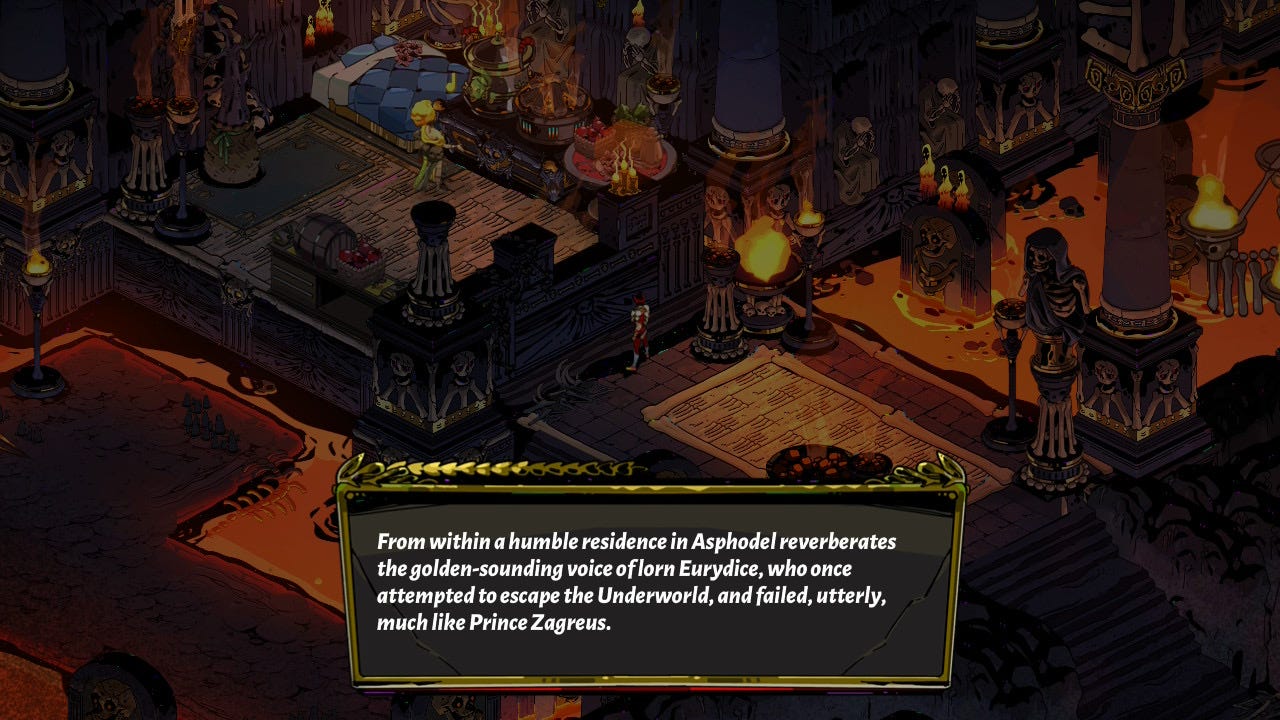

The emphasis on Eurydice’s agency continues in the video game Hades (2020). As a rogue-lite video game,27 players are tasked with repeatedly pushing their way through enemy-filled levels and collecting power ups. Every time the player avatar Zagreus dies and resurrects in the House of Hades (which happens quite often), the player loses nearly all their progress but gains knowledge of new enemies and strategies for advancing further in subsequent attempts.28 Upon defeating the Fury Megaera and reaching the chthonic realm of Asphodel, the player faces harder enemies than before. Sometimes, however, the player is allowed a moment of respite by entering an enemy-free chamber (see Example 2). The first time Zagreus enters this room, he’s dumbfounded to hear singing: “What . . . singing . . . here?”29 We’ve come to expect that if there’s singing, it’s Orpheus. In this case, though, it’s Eurydice. Noted by Demetrius Shahmehri, Eurydice’s is the first singing voice the player hears in Hades.30 Eurydice’s song “Good Riddance” interrupts the musical flow of the game in which some really banging rock tunes crescendo from room to room. “Good Riddance,” on the other hand, is slow and ruminative, and in taking the player off-guard, it forces the player to pause and listen.

In Hades, Eurydice’s fleetingly acousmatic voice travels not on the screen’s surface but rather between screen and player, so that Zagreus and player both pause, suspended in a moment of shared listening. In Metamorphoses, after Orpheus loses Eurydice for the last time, Ovid details that Orpheus’s final songs in lamentation move wild animals, trees, and even stones to listen. This parallels the effect her song had on me, subduing Zagreus and me and countless other players as we ransacked the Underworld. Hades does what any great work in myth must do: reworking myth in the image of our own, or a desired present, building thoughtfully and lovingly on the world of Greek myth, suffusing it with an egalitarian, polyphonic spirit.31

In Hades, it is Eurydice that possesses the Orphic voice that has always been attributed to male characters, “where it has never solely belonged anyway, either in theory or practice.”32 With the music of Eurydice and the inversion of her and Orpheus’s myth, Hades reworks ancient legends in an effort to present more representational voices.33

Conclusion

Music historians have long written about the prevalence of myths and the stories of ancient gods in music. With the emergence of the galant style at the beginning of the Classical period, a tension arose between the longstanding tradition of adapting legends and the push to adapt more human stories. This spawned the genre of opera buffa (funny opera) that made everyday characters its subject matter, as opposed to opera seria (serious opera) that remained focused on legend. These two genres evolved together and were often even programmed together, but for some time, legendary and human stories remained functionally separate. While I could cite actual scholars on this topic, I think the film Amadeus (1984) sums up the argument in favor of maintaining legend fairly well:

MOZART: Why must we go on forever writing only about gods and legends!?

van SWIETEN: Because they do. They go on forever. At least what they represent: the eternal in us. Opera is here to ennoble us, Mozart—you and me, just the same as His Majesty.34

Even though gods are by definition above humanity, there is something innately human about how their stories are told. Yeah, they’re old and often seem ludicrous, but like Shakespeare’s plays, they remain endlessly applicable to the human experience.

Orpheus and Eurydice is a story about humanity’s capability for immense love and grief. Terry Cavanagh’s Orphic video game Don’t Look Back (2009) represents the cyclical nature of grief quite well. The player character begins by staring at a grave and subsequently going underground. After facing hellish monsters, finding Eurydice, and returning back to the surface, the player’s progress is undone by the gaze of another iteration of the player character, still at the grave. Here, the Orpheus/Eurydice story is reworked to reflect the inner experience of grief and the plight of trying to bargain one’s way out of it. As in this example and those of Orphée aux enfers and Hades, we see how myth keeps its relevance by adapting to more relevant contexts.

But the Orpheus myth is also at the heart of song. As Orpheus did, musicians of all eras have wielded music as a power for storytelling and personal expression. When Lady Gaga implores her partner to wrap a blade of grass around her finger,35 there is Orpheus rejoicing in his marriage to Eurydice. When video game players (through the musician-hero Link) perform “Zelda’s Lullaby” to magically propel the Ferry to the Other World,36 there is Orpheus singing and charming Charon, the Stygian ferryman. When medieval troubadours sang of love and loss, there was Orpheus’s joy and grief. Time and time again, whenever there’s music and singing, it’s Orpheus and Eurydice.

I would love a comment! And also for you to share this! And subscribe to this blog if you haven’t already!

Bibliographies

All websites last accessed June 15, 2025.

Non-Fiction

Abbot, Graham. “The Inspiration of Orpheus.” Graham’s Music. 2020. https://www.grahamsmusic.net/post/the-inspiration-of-orpheus

Bacon, Helen H. “The Chorus in Greek Life and Drama.” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 3, no. 1 (1994/5); 6–24.

Blocker, Déborah. “The Accademia degli Alterati and the Invention of a New Form of Dramatic Experience: Myth, Allegory, and Theory in Jacopo Peri’s and Ottavio Rinuccini’s Euridice (1600).” In Dramatic Experience: The Poetics of Drama and the Early Modern Public Sphere(s). Edited by Katja Gvozdeva, Tatiana Korneeva, and Kirill Ospovat, 77–117. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

Boynton, Susan. “The source and significance of the Orpheus myth in Musica Enchiriadis and Regino of Prüm’s Epistola de harmonica institutione.” Early Music History 18 (1999): 47–74.

Carr, Maureen A. Multiple Masks: Neoclassicism in Stravinsky’s Works on Greek Subjects. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2002.

Carter, Tim. “Claudio Monteverdi.” In The Viking Opera Guide, edited by Amanda Holden, Nicholas Kenyon, and Stephen Walsh, 676–83. London: Viking, 1993.

———. “‘In questo lieto e fortunato giorno’: ‘parlare’ e ‘cantare’ nell’Orfeo di Monteverdi.” In In questi ameni luoghi: Intorno a “Orfeo.” Edited by Liana Püschel and Luca Rossetto Casel, 29–42. Turin, IT: Associazione Arianna, 2018.

Coronis, Athena. “Sarah Ruhl’s Eurydice: A Dramatic Study of the Orpheus Myth in Reverse.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies. Supplement, no. 126 (2013): 299–315.

DePrado, Jarrod. “Two Roads to Hell: Rebirth and Relevance in Musical Adaptations of Katabatic Myth.” Mythlore 42, no. 2 (144) (2024): 85–102.

Fattor, Hannah. Rain Inside the Elevator: Dualities in the Plays of Sarah Ruhl As Seen Through the Lens of Ancient Greek Theatre. Essay, 2012. https://jstor.org/stable/community.36514441.

Hamilton, Edith. Mythology. Illustrated by Steele Savage. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1942.

Hill, Christopher, Stephanie Lind, Silvia Mantilla-Wright, and Demetrius Shahmehri. “Introduction: The Sound and Music of Hades.” Journal of Sound and Music in Games 6, no. 1 (2025): 1–7.

Kamp, Michiel. “Introduction: Towards a Phenomenology of Video Game Music.” In Four Ways of Hearing Video Game Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1–28.

Kirkwood, G. M. A Short Guide to Classical Mythology. Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci, 1995.

———. Early Greek Monody: The History of a Poetic Type. Ithaca, NY and London: Cornell University Press

Leopold, Silke. Monteverdi: Music in Transition. Translated by Anne Smith. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991.

Murdoch, Brian O. “Denial and Acceptance: A Core Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice in the Modern Lyric.” Mythlore 42, no. 2 (144) (2024): 43–60.

Nelson, Will. “Ex Musica, Magia: The Power of Music in The Lord of the Rings, The Legend of Zelda, and Dungeons & Dragons.” Will’s Ludomusings. Substack, June 9, 2025. https://whnelson.substack.com/p/ex-musica-magia.

———. “Monteverdi’s Humanist Harmonies: Humanist Philosophy in L’Orfeo and The Fifth Book of Madrigals.” Graduate application paper, 2024. Unpublished manuscript.

Randel, Julia. “Un-Voicing Orpheus: The Powers of Music in Stravinsky and Balanchine’s ‘Greek’ Ballets.” The Opera Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2013): 101–145.

Shahmehri, Demetrius. “Eurydice Sings: Revoicing a Musical Myth in Hades.” Journal of Sound and Music in Games 6, no. 1 (2025): 66–82.

Sword, Helen. “Orpheus and Eurydice in the Twentieth Century: Lawrence, H. D., and the Poetics of the Turn.” Twentieth Century Literature 35, no. 4 (1989): 407–428.

Traubner, Richard. “Jacques Offenbach.” In The Viking Opera Guide, edited by Amanda Holden, Nicholas Kenyon, and Stephen Walsh, 734–6. London: Viking, 1993.

Weiner, Albert. “The Function of the Greek Tragic Chorus.” Theatre Journal 32, no. 2 (1980): 205–212.

Fiction

Tolkien, J.R.R. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1975.

———. The Silmarillion. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. New York: Ballantine Books, 1979.

Film

Camus, Marchel, director. Orfeu Negro. Music by Luiz Bonfá and Antônio Carlos Jobim. Paris: Dispat Films, 1959.

Forman, Miloš, director. Amadeus: Director’s Cut. Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Originally released 1984. Burbank: Warner Bros., 2002.

Sciamma, Céline, director. Portrait de la jeune fille en feu. Music by Para One and Arthur Simonini. Paris: Lillies Films, 2019.

Waititi, Taika, director. Thor: Ragnarok. Music by Mark Mothersbaugh. Burbank: Marvel Studios, 2017.

Music (Operas, Ballets, Albums, Libretti, etc.)

Aucoin, Matthew. Eurydice. Text by Sarah Ruhl (2003). 2020.

Caccini, Giulio, and Jacopo Peri. Euridice. Libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini. 1600.

Gaga, Lady, Andrew Watt, Henry Walter, and Michael Polansky. “Blade of Grass.” Track 13 on Mayhem. Santa Monica, CA: Streamline and Interscope, 2025.

Gluck, Christoph Willibald. Orfeo ed Euridice. Libretto by Ranieri de’ Calzabigi. 1762.

Hackett, Steve. Metamorpheus. 2005.

Mitchell, Anaïs. Hadestown. Book, music, and lyrics by Anaïs Mitchell. 2006.

Monteverdi, Claudio. L’Orfeo. Libretto by Alessandro Striggio. 1607.

Offenbach, Jacques. Orphée aux enfers. Libretto by Hector Crémieux and Ludovic Halévy. 1858.

Ruhl, Sarah. Eurydice. Text by Sarah Ruhl. 2003.

Stravinsky, Igor. Orpheus. Scenario by Igor Stravinsky and George Balanchine. 1948.

Striggio, Alessandro. L’Orfeo. Libretto. Translated by Gilbert Blin (2012). Early Music Vancouver Masterworks Series. Vancouver: Early Music Vancouver, 2017/18. PDF.

Testament. Orpheus in the Record Shop. Text by Testament. Additional music by Taz Modi. 2020.

Ludography

Cavanagh, Terry, director. Don’t Look Back. Adobe Flash, iOS, Android, and others. Developed by Distractionware. Music by Terry Cavanagh. London: Kongregate, 2009.

Kasavin, Greg, director. Hades. Windows, macOS, Nintendo Switch, and others. Developed by Supergiant Games. Music by Darren Korb. San Francisco: Supergiant Games, 2020.

Miyamoto, Shigeru, director. The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. Nintendo 64. Developed by Nintendo EAD. Music by Koji Kondo. Kyoto: Nintendo, 1998.

Appendix

Disembarking on the Ferry to the Other World in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998). Gameplay recorded by author. Emulated through Nintendo 64 – Nintendo Classics on Nintendo Switch 2.

Will Nelson, “Ex Musica Magia: The Power of Music in The Lord of the Rings, The Legend of Zelda, and Dungeons & Dragons,” Will’s Ludomusings, Substack, June 9, 2025. https://whnelson.substack.com/p/ex-musica-magia. Under the heading “Beren and Lúthien.”

Later published as J.R.R. Tolkien, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo, ed. Christopher Tolkien (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1975): 133–148.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Silmarillion, ed. Christopher Tolkien (New York: Ballantine Books, 1979), (of parentage) 199, (of descent and music) 218–221, and (of mortality and doom) 226–228.

That’s a lie; it was. I love Tolkien and I’m not ashamed of it.

Rainer Maria Rilke, “Errichtet keinen Denkstein,” in Duineser Elegien und Die Sonette an Orpheus (Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1974), 53. Die Sonette were originally published in 1923. Translated by yours truly.

Compare with Lúthien’s parentage.

Edith Hamilton, Mythology, ill. by Steele Savage (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1942), 103.

Ibid., 104.

G. M. Kirkwood, A Short Guide to Classical Mythology (Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci, 1995), 72.

I jest. In Ottavio Rinuccini’s libretto for Euridice, the end is not tragic. Orpheus doesn’t look back and he and Eurydice rejoice upon leaving the Underworld. This is kind of a disappointing ending, but Peri was commissioned to write the opera for a Medici family wedding, so the original marriage-ending conclusion to the myth wouldn’t have been very appropriate.

Tim Carter, “Monteverdi,” in The Viking Opera Guide, ed. by Amanda Holden, Nicholas Kenyon, and Stephen Walsh (London: Viking, 1993), 677.

Ibid.

Alessandro Striggio, L’Orfeo, libretto, trans. Gilbert Blin (2012), Early Music Vancouver Masterworks Series (Vancouver: Early Music Vancouver, 2017/18), 2. PDF.

L’Orfeo and other Orphic operas also present an odd paradox: how does the audience know when the characters are singing within the confines of operatic structure or singing as part of the story? This is addressed at length in Tim Carter, “‘In questo lieto e fortunato giorno’: ‘parlare’ e ‘cantare’ nell’Orfeo di Monteverdi,” in In questi ameni luoghi: Intorno a “Orfeo” ed. Liana Püschel and Luca Rossetto Casel (Turin: Associazione Arianna, 2018), 29–42. In essence, Carter discusses how Monteverdi and librettist Alessandro Striggio use textual and musical signposts to help the audience recognize when characters are singing diegetically.

Some musicologists are a little nit-picky about the “early Baroque” period really being the Mannerist period. I’m not going to get into that whole thing, but if you’re interested see Tim Carter, “Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque,” in The Cambridge Companion to Seventeenth-Century Music, ed. Tim Carter and John Butt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 1–26.

Silke Leopold, Monteverdi: Music in Transition, translated by Anne Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994), 43–44. The “ancient monody” discussed by Leopold is otherwise known as Greek lyric poetry, a medium in which oral traditions were passed on through song and lyre accompaniment.

Will Nelson, “Monteverdi’s Humanist Harmonies: Humanist Philosophy in L’Orfeo and The Fifth Book of Madrigals,” graduate application paper, 2024. Unpublished manuscript, 3.

More nuanced views of this Ancient Greek tradition are offered in Albert Weiner, “The Function of the Greek Tragic Chorus,” Theatre Journal 32, no. 2 (1980): 205–212; and Helen H. Bacon, “The Chorus in Greek Life and Drama,” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 3, no. 1 (1994/5): 6–24. One of my favorite modern interpretations of Ancient Greek plays and tragic choruses appears in Taika Waititi, dir., Thor: Ragnarok (Burbank: Marvel Studios, 2017), film, 0:09:51–0:11:47. It’s not entirely accurate because the only commentary the chorus gives is somber ahh-ing, but Waititi’s silly way of blending Ancient Greek traditions into a story inspired by Norse mythology is very fun to me.

One of these bits of excess he saw was the da capo aria form. He wanted the plot to carry on without needing to go back and forth between musical and textual ideas.

It is notable also for removing the voice from the famously vocal Orpheus. This is elaborated in Julia Randel, “Un-Voicing Orpheus: The Powers of Music in Stravinsky and Balanchine’s ‘Greek’ Ballets,” The Opera Quarterly 29, no. 2 (2013), 101–145.

Jarrod DePrado, “Two Roads to Hell: Rebirth and Relevance in Musical Adaptations of Katabatic Myth,” Mythlore 42, no. 2 (144) (2024), 99.

In fact, her glossary entry is one of the shortest in Kirkwood, A Short Guide to Classical Mythology, 42. The entry is merely “Eurydice was the wife of Orpheus.” The entry for Orpheus, which I cited earlier, is about forty times longer.

Helen Sword, “Orpheus and Eurydice in the Twentieth Century: Lawrence, H. D., and the Poetics of the Turn,” Twentieth Century Literature 35, no. 4 (1989), 408.

Richard Traubner, “Jacques Offenbach,” in The Viking Opera Guide, ed. Amanda Holden, Nicholas Kenyon, and Stepehen Walsh (London: Viking, 1993), 735.

The only character unhappy by Eurydice’s fate is called Public Opinion, Offenbach’s parody of the Chorus. Public Opinion is played by only one person, and in opposition to the old traditions of the Chorus, is there to intervene in the story, not just to comment on its happenings.

Hanna Fattor, Rain Inside the Elevator: Dualities in the Plays of Sarah Ruhl as Seen Through the Lens of Ancient Greek Theatre, essay (2012), 9. https://jstor.org/stable/community.36514441.

“Roguelike” games are those that resemble the game Rogue (1980). In Rogue, the death of the player character is final. Players restart the game each time they lose. Think of it like hardcore mode in Minecraft (2011). “Rogue-lite” games are a little more forgiving. The player restarts the game after each death, but maintains some items and progression. Restarting isn’t from scratch in Rogue-likes.

This is rather Sisyphian, which is fitting because you can meet Sisyphus in the game.

Something cool about Zagreus: his voice lines were provided by the game’s composer, Darren Korb.

Demetrius Shahmehri, “Eurydice Sings: Revoicing a Musical Myth in Hades,” Journal of Sound and Music in Games 6, no. 1 (2025), 67.

Ibid., 81.

Ibid.

(Not music alert!): Madeline Miller’s books Song of Achilles (2011) and Circe (2018) are other great examples of this drive to modernize myth with greater representation of marginalized communities.

Miloš Forman, dir., Amadeus: Director’s Cut, originally released 1984 (Burbank: Warner Bros., 2002), 1:38:37–1:39:00.

Lady Gaga, Andrew Watt, Henry Walter, and Michael Polansky, “Blade of Grass,” track 13 on Mayhem (Santa Monica, CA: Streamline and Interscope, 2025).

Shigeru Miyamoto, dir., The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, developed by Nintendo EAD, music by Koji Kondo (Kyoto: Nintendo, 1998), Shadow Temple sequence. See appendix.