Semiotics in Audiovisual Media and Video Games

As the study of signs, symbols, and their interpretation, semiotics is integral to software design and digital media. In aural semiotics, we typically distinguish between two primary categories: auditory icons, which resemble natural sounds, and earcons, which are abstract sounds learned to represent actions within an interface.1 The fwshhk! sound of a computer’s Recycle Bin/Trash being emptied is an example of an auditory icon; the naturalistic sound signifies crumpling paper and emptying the trash. When pressing a disabled key on a MacBook, an error beep sounds that signals to a computer user that the button they’re pressing does not function. Since this beep doesn’t represent a real-world sound,2 it acts as an earcon that users learn to associate the sound with invalid actions.

When Zach Whalen gave ludomusicology its intellectual impetus with his 2004 article “Play Along: An Approach to Videogame Music,” he established it as a field in close dialogue with semiotics. A connection to semiotics makes sense for video games: the medium overtly operates on systems of signifiers and signifieds. In Elden Ring (2022) and other FromSoftware games, for example, a red bar in the top left of the screen signifies the player-character’s health (signified) and its rapid depletion signifies the severe difficulty of the game (see Example 1).

Without outright framing game sounds as signifiers with corresponding signifieds, Whalen identifies ways in which sounds signal changes in game states. One of these ways is through mickey-mousing, a term borrowed from film studies that describes cartoonish synchronization of sounds and images on a screen.3 In Super Mario Bros. (1985), a rising glissando sounds simultaneously with Mario’s jumps.4 As an earcon, players are trained to associate the glissando with the act of jumping, and over time, the upward glide of the earcon comes to signify the upward motion of the Jumpman’s leaps.

Another way Whalen describes is through the dichotomy of what he terms “safety states” and “danger states.”5 The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) is an early example of a game with fluid movement between sound files for safety and danger states. By rendering audio through the CPU rather than generating sounds on a dedicated sound chip,6 the Nintendo 64 was able to seamlessly transition between safety and danger sound files whenever the player-character Link approached or moved away from enemies in Ocarina of Time. The shift from normal environmental music toward music more worthy of battle “heightens the drama of the conflict and alerts the player to more focused performance.”7 Phenomenally, the moment of the shift from one state to the other is the most significant part of the semiotic event:

It is merely the recognition of a change in cue that we need to know there is danger, after which the music no longer requires our (semiotic) attention. To summarize, semiotic music has two characteristics: it is unimportant what it sounds like apart from the fact that it sounds different from its context, and it requires only the smallest moment of attention.8

Kamp highlights that, once players are familiar with signifiers, they function instantaneously and don’t demand much attention.

All of these signifiers and signifieds serve to heighten immersion in game worlds. The more players attend to musical signifiers and come to understand their signifieds, the more they become accustomed to a game’s aural framework. And as we’ve seen, when a semiotic system has been learned, recognition of the signified becomes instantaneous. It is in this instant of attention to a signifier and signified that immersion can be bolstered or undermined.

Thanks for reading another long post! I know you haven’t gotten to the actual long part yet, but you can do the whole subscribing thing here if you haven’t already. I would also love to hear from you, too! Leave a comment or send me a message! Also share this with people you think would get a kick out of it. Buttons for all that stuff will be at the bottom of the essay, so you have to read the whole thing.

All the best as you finish this essay,

Will

Creating Immersion

When one thinks about immersion in video games, they generally think in terms of losing themselves in gameplay and momentarily forgetting that they’re playing a game. But what immersion requires and implies are rather nebulous. In an early view on game immersion, Laura Ermi and Frans Mäyrä offered a framework for immersion based on three dimensions of gameplay experience: sensory, challenge-based, and imaginative immersion.9 Gordon Calleja goes into further specifics in his identification of six components of “player involvement” based on experiential phenomena. Namely, these phenomena are kinesthetic, spatial, shared, narrative, affective, and ludic involvement with a game.10 More recently, Isabella van Elferen has put forward a game-audio immersion framework as an extension of the SCI model and Gordon Calleja’s components of player involvement. Van Elferen’s ALI model focuses on three components of “musical game involvement”: affect (one’s personal investment in game audio), literacy (one’s ability to hear and interpret game audio), and interaction (one’s engagement in music-making practices within a game’s dynamic audio).11

The Mario Kart series (1992–) is overflowing with opportunities for immersion because there is always so much happening during a race and the games require a player’s full attention if they want to take the first place title. As the most recent entry in the series, Mario Kart World (2025) carries on its predecessors’ blend of immersive music and semiotic sound effects. See Video Example 1 below for a brief, yet semiotically dense example of a race in Mario Kart World:

Video Example 1: Racing from Cheep Cheep Falls to Dandelion Depths in Mario Kart World. Captured by author on Nintendo Switch 2.

There are so many signifiers and signifieds going on in this example! To name only a few, there are slot machine-like sounds for item collection, alarms that warn of an incoming red shell attack, chimes that signal coin pickups, and Mario’s yelps that indicate he got hit by a weapon. All of these create a dynamic musical architecture that demands immersion.12 From background music that pumps players up for a race to constantly instigating and interpreting sound effects, Mario Kart games have all the right ingredients to fully engross a player in the gameplay.

Disrupting Immersion

But some strategies for achieving immersion can backfire. Melanie Fritsch and Tim Summers note, for example, that:

Interactivity may be an essential quality of games, but this does not necessarily mean that music has to respond closely to the gameplay, nor that a more reactive score is intrinsically better than non-reactive music. Music that jumps rapidly between different sections, reacting to every single occurrence in a game can be annoying or even ridiculous. Abrupt and awkward musical transitions can draw unwanted attention to the implementation.13

A notorious example of this awkward implementation (at least for me) exists in Lego Star Wars: The Complete Saga (2007). The game has been lauded since its original release for heightening the campy humor already existent in George Lucas’s six Star Wars films (1977–2005),14 and the game’s music is largely sourced from John Williams’s original scores for the saga. Lego Star Wars makes use of safety and danger state music, using slower, quieter pieces from Williams’s scores for peaceful moments and battle music for dangerous moments. Even in a galaxy built by Lego bricks, wandering the deserts of Tatooine looking for C-3PO and R2-D2 while the music from “The Desert and the Robot Auction” plays in the background makes it feel like you’re Luke Skywalker looking to purchase a couple droids.

But onto the awkward bit: when playing through the games’ various levels, there is a near-constant jingling sound woven into the environmental music that is entirely disjunct (a term borrowed from Elizabeth Medina-Gray)15 with the music of Williams (watch Video Example 2).

Video Example 2: Jingling sounds permeate the music of “Imperial Attack” as a Lego Princess Leia attempts to escape the Tantive IV. Captured by author on Xbox Series S/X.

The jingles feel like they are meant to be signifying something, but looking around the level, it just seems like strange sound design. That’s what I thought until I played the game again for my example. Throughout Lego Star Wars, the player has the option to gather collectibles known as Minikits that are scattered around each level. Collecting all ten Minikits in a level grants the player the ability to construct a small Lego set within the game that gets them one step closer to 100%-completion. The jingling that seems to plague each level is supposed to signal to the player that they are in the vicinity of a Minikit. By not explaining the signal, however, Lego Star Wars turns these jingles into an unestablished or “broken” signal.16 This broken signal interrupts the player’s immersion by forcing them to think about the game design and whether the jingling is a response to their actions. Why is there this jingling? Is it part of the background music? Does it mean something? In this moment, the player’s attention is shifted from gameplay to game mechanics and Lego Star Wars becomes a game of finding the source of the jingling rather than being about dismantling the Galactic Empire Lego brick-by-Lego brick.

Low-Health Alarms

Shifting attention by way of disrupting immersion can be a powerful tool for game designers, though. Sonic signals like low-health alarms definitely cause disjunction within modular sound design, but are used to warn the player of the danger they’re in. In The Legend of Zelda (1986), the low-health alarm is anything but subtle. On a sound chip only capable of producing four (or five) sounds at a time, the alarm forces one of those sounds to stop. This completely alters the musical architecture and urges the player to shift their attention toward self-preservation as a means to continue the game and thereby relieve the disjunction (see Video Example 3).17

Video Example 3. The low-health alarm in The Legend of Zelda. Captured by author on Nintendo Switch 2 via Nintendo Switch Online.18

The twin games Pokémon Black Version and Pokémon White Version (2010) handle the low-health alarm quite differently. In previous entries to the Pokémon series (1996–), the alarm operates in much the same way as in The Legend of Zelda, but without the need to remove any of the game’s Pokémon battle music. Rather, the module for the alarm is placed into the entirety of the musical architecture. This still causes disjunction and signals to the player that their Pokémon’s doom is nigh and they should probably throw a health potion their way. In Black and White, however, the alarm completely cuts out the battle music. All the player hears is the alarm until a new battle music begins with the alarm integrated as its rhythmic backbone (listen to Audio Example). The new battle music is a sort of even-more-danger state and signals the dire situation of the battle, strengthening the player’s determination and sharpening their attention toward helping their Pokémon before they faint.

Audio Example. The “Low HP” theme from Pokémon Black and White.

A final low-health alarm I would like to look at appears in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017). We’ve already seen how the alarm functions in the first game of the Zelda series in which it sounds rather obnoxiously over the game’s music. Unfortunately for players who consistently have low health (me included), this became commonplace in Zelda titles until the release of Breath of the Wild. As a launch title on the Nintendo Switch (2017), Breath of the Wild was poised to shirk tradition and bring Nintendo millions of new fans. This was manifest in many ways, from Link no longer donning his green tunic to the game being set in a massive open world with a nonlinear story. The game is sonically very impressive, too, and while I could talk about how every piece of armor and ground texture affects the sound of Link’s footsteps (a topic for another time), the low-health alarm is of the most importance to the current essay. In Breath of the Wild, the alarm is significantly less obtrusive than in previous titles. Rather than beeping loudly and incessantly, there is one alarm followed by quiet, intermittent pulses that blend into the game’s sparse, atmospheric soundscape (see Video Example 4). The pulses remain until the player has regained health for Link, but they indicate that the player should remain calm and think through their actions carefully. This is echoed by one of the game’s tips that appears during loading screens: “Instead of throwing yourself at enemies over and over to no avail, try cooking special dishes and elixirs to give yourself better defense, extra damage, or more hearts.”19

Video Example 4. Taking significant damage in Breath of the Wild, beginning the low-health alarm. Captured by author on Nintendo Switch 2.

Beyond low-health alarms, immersion can also be manipulated with abrupt shifts of music. We saw this to an extent in the Low HP theme from Pokémon Black and White, but I think a more nuanced use of this method is found in Hades (2020). On the player’s quest to leave the realm of Hades, they must pass through several levels, fighting dozens of enemies in each level. The game is intense, and Darren Korb’s rocking, frenetic score reflects the intensity perfectly. It almost always feels like the player is in danger, so when the electric guitars stop on a floor in Asphodel and slow, somber singing starts, the player may be understandably taken aback. Here, the player meets the dryad Eurydice (of Orpheus and Eurydice fame) whose song reflects her woeful, solitary existence in the Underworld. In an instant, the player’s attention is shifted from the intense battles they’ve faced up until that point to the story of Eurydice and the help she offers them on their quest. This abrupt change is an example of what Clint Hocking calls ludonarrative dissonance, or a disconnect between core gameplay and story.20 Hocking describes a case in which this dissonance reduces a game’s immersive qualities, but in the case of Hades, ludonarrative dissonance is not an experience-destroying flaw. The sudden focus on the voice of Eurydice is jarring and makes the player pause:

At the very least, the singing voice causes the player a moment of surprise. But the moment is so startling that I suspect most players lingered here at least a little bit, forced at least to pause, and at most to listen to the song and reflect on its source. Why is this moment so powerful? And what is the significance of Eurydice’s song? . . .

Whereas in most video games the power of the singing voice comes from its ability to alter the game world diegetically, Eurydice’s song transcends the screen to disrupt the processes of the game itself, as it is experienced by the player. The song leaves its listeners, like Orpheus’s audiences in Ovid, subdued and transfigured by the singing voice.21

Like strong dissonances in classical music adding drama and putting consonances into context, this ludonarrative dissonance reflected by the sudden change in musical behavior is a source of intrigue and rewrites what it means to be immersed in the gameplay of Hades.

The examples we just went through show how semiotic disruptions to game audio immersion (disruptive beeps, abrupt shifts in music, and soft cues) can be vehicles by which game designers reframe immersion and keep players engaged. In the next section, I want to take a look at how these disruptions can just be plain annoying.

Navi in Ocarina of Time: “Why Not Take a Break?”

As the first three-dimensional Zelda game,22 The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time needed a way to navigate all three of those dimensions. In order to efficiently move the game’s camera and place the focus on specific points of interest, the developers devised the concept of Z-targeting. By pressing the Z button on the Nintendo 64 controller, the camera would reorient itself in one of two ways: if no point of interest was nearby, the camera would snap behind Link; if a point of interest was present, the camera would lock onto it. But being Nintendo, there needed to be a fun, diegetic reason for how Link identifies points of interest. Thus, the fairy companion Navi was born. Whenever Link moves near enemies or certain objects, Navi flies over to them, signaling to the player that they can Z-target that enemy/object. Navi exclaims Watch out! or Look! any time the player Z-targets an enemy (signifying that the camera has locked in on the enemy), and an on-screen icon indicates that the player can press a button to speak with Navi for information on the enemy (watch Video Example 5). The system of Z-targeting an enemy and (optionally) having Navi describe it helps the player make sense of battling enemies in a three-dimensional space and facilitates immersion in battle scenarios.

Video Example 5. As I Z-target a blue tektite, Navi says “Watch out!” and offers her advice. In English, Navi says, “A blue Tektite! You have slim chances of catching it in the water. Lure it to land!” I then fumble to defeat the tektite because I don’t know how to control the game on the Switch. Captured by author on Nintendo Switch 2 via Nintendo Switch Online.

That would be a great system if that was the only time Navi spoke. Voices are inherently more ear-grabbing than the vast majority of sounds, and apart from some grunts and yelps, Navi’s voice is the only voice heard in Ocarina of Time. This makes her frequent Hey!’s and Listen!’s all the more noticable and distracting from gameplay. In his companion to the music of Ocarina of Time, Tim Summers begins with a description of Navi’s voice:

Hey! Listen! Navi, my fairy companion, exclaims. Again.

There isn’t much recorded speech in [Ocarina of Time], but Navi has a voice. She is given a limited set of important phrases. These few words spoken by our hero’s sidekick are repeated so often that they become etched into the player’s memory.23

Often repeated they are. If the player doesn’t move directly from one story beat to the other, Navi will begin to yell Hey! at the player at regular intervals and does not stop until Link has either reached the next important location or the player gives in and talks to her. When pressing the button to talk, Navi yells Listen! as if she hasn’t already forced us to talk to her. When the player relents and speaks with Navi, she will try to advise the player on what next steps they should take. In Video Example 6 (below), this advice is merely “What would Saria say if she knew we were saving Hyrule?”

Video Example 6. A peaceful walk through Kakariko Village is interrupted by Navi’s “Hey! Listen!” Captured by author on Nintendo Switch 2 via Nintendo Switch Online.

To players that have become accustomed to Navi’s voice sounding when targeting enemies, this may seem like a misfire. If there aren’t enemies around, why is Navi talking? Is there an enemy I just can’t see? Thus, if a player is confused by Navi’s voice, their immersion may also be confused. But when players have learned to associate this signal with mostly useless advice from Navi, it becomes a source of annoyance that detracts from Ocarina of Time’s otherwise highly immersive gameplay.

Much to the woe of Zelda enjoyers, Navi still shouts at Link in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time 3D (2011)—a remake of the Nintendo 64 game for the Nintendo 3DS. Some even believe that Navi became even more annoying on the 3DS. In Nintendo’s now defunct magazine Nintendo Power, editor-in-chief Chris Slate wrote in a review of Ocarina of Time 3D:

There are so many clear improvements in the N3DS release that it’s tough to quibble, but I could do without the extra comments from Link’s fairy companion Navi, whose distracting alerts were already borderline annoying in the original game. While she does sometimes give useful hints, more often than not she interrupts the game to repeatedly suggest that you take a break from playing or go watch a hint movie. Turning to her for advice when I’m hopelessly stuck, only to get tips like “Keep moving!” or “This barrier is blocking the door! There must be some secret to opening it!” is like pouring salt in a wound.24

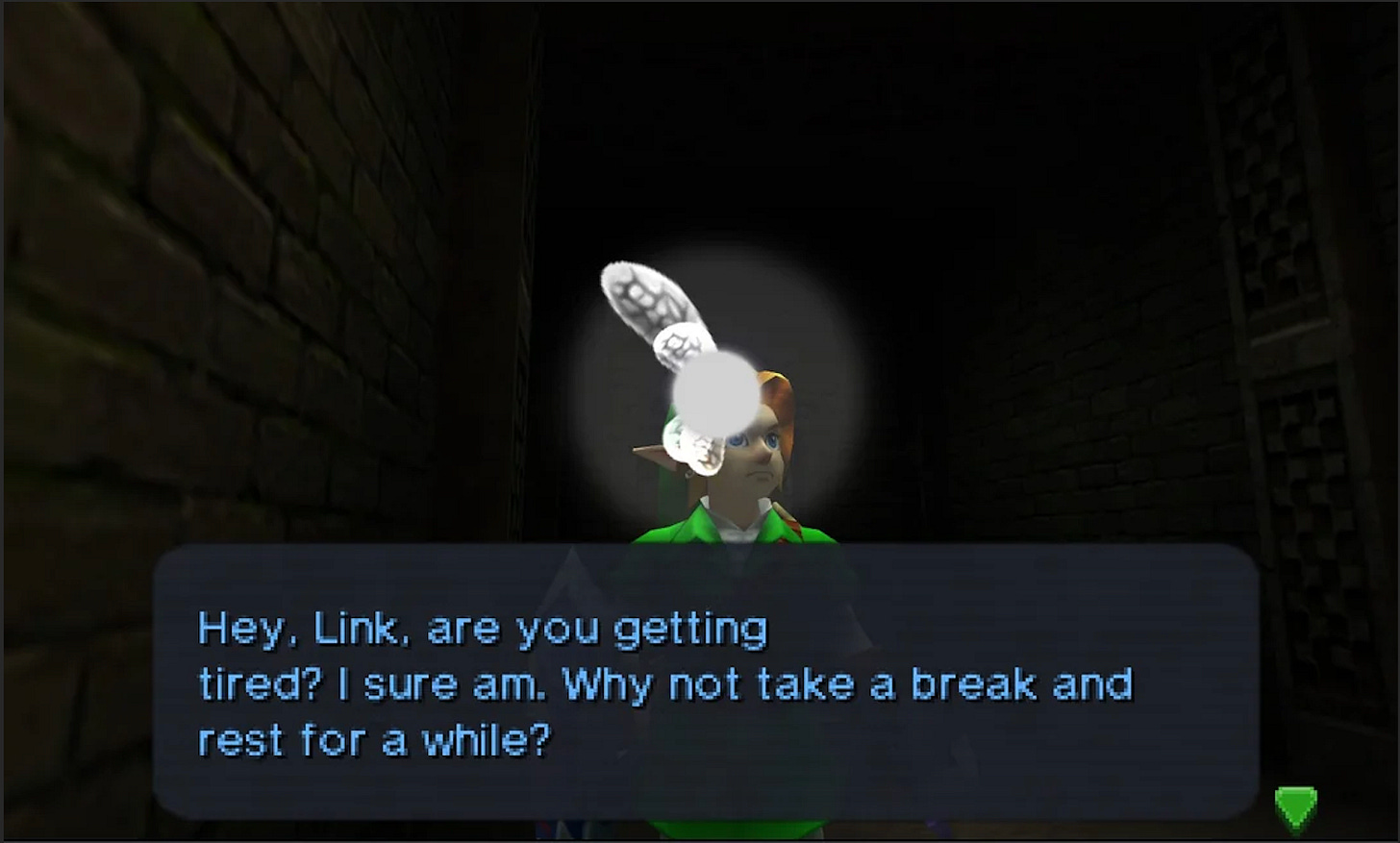

Navi continues to disrupt the immersive music of Ocarina of Time in the remake, but additional messages have been added. As Slate noted, Navi has a tendency in Ocarina of Time 3D to suggest the player watch a hint movie, a feature added to the remake to help players manage tricky parts of the game. These hint movies arguably make Navi’s original role redundant and should have made her Hey! Listen!’s more sparse. Nonetheless, Navi continues to offer her advice in the remake. In addition, a new message is added that sounds periodically in which Navi expresses her exhaustion and suggests that the player take a break from the game (see Example 2). This message is an open affront to any immersion the player had acquired up to that point. Even more than Navi’s alerts on the Nintendo 64, these meta-ludic pleas for the player to take a break rip the player out of the game.

This served a rather healthy purpose for players of the Nintendo 3DS, however. The handheld system’s reliance on stereoscopic visuals as a means to achieve three-dimensional images caused eye-strain after prolonged playing sessions. Several games on the system include similar messages to suggest the player put the 3DS down for a while. Nearly every time the player saves their game in The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds (2013), the game displays a message that reads, “You’ve been playing for awhile. Why not take a break?”25 Game publishers have long recognized the need for players to take breaks from games. In EarthBound (1994), the player-character regularly receives calls on his phone with messages from his father to be sure to take breaks.26 After repeated instances of this, the phone call sound becomes a signal to put the controller down and go outside. Similar messages to the ones from the above games appear in several instructional booklets from the eras of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) and the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES). The following appears in a booklet for the SNES:

Some people may experience fatigue or discomfort after playing for a long time. Regardless of how you feel, you should ALWAYS take a 10 to 15 minute break every hour while playing. . . . If you continue to experience soreness or discomfort during or after play, listen to the signals your body is giving you.27

If bodily semiotics fail, though, Navi and other annoying sounds are good aural semiotic devices that remind us to go outside and touch grass every now and then.

Conclusion

In all of these examples, we’ve seen how aural semiotics have the ability to shape player immersion and to disrupt it. Auditory icons, earcons, musical gestures, and so many other forms of signals are all part of a video game’s musical architecture that guide players and help them interpret game functions. In learning these functions, players can transcend game mechanics and become immersed in gameplay. But signals can become taxing if they are overused or aren’t properly learned. The broken Minikit signal in Lego Star Wars and Navi’s incessant attempts to give Link advice take a toll on the overall immersive quality of a game. But as we’ve seen in the example of Hades’s Eurydice and in Nintendo’s meta-diegetic calls for players to take breaks, these immersion disruptors can be beneficial both for the game narratives and for the wellbeing of the player outside of the game world. Disruption can be as powerful a tool as immersion and the same semiotic vehicles that create immersion can also be disruptive.

References

All websites last accessed June 22, 2025.

Bibliography

Calleja, Gordon. In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Collins, Karen. Game Sound: An Introduction to the History, Theory, and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008.

Elferen, Isabella van. “Analysing Game Musical Immersion: The ALI Model.” In Ludomusicology: Approaches to Video Game Music, edited by Michiel Kamp, Tim Summers, and Mark Sweeney, 32–52. Bristol, CT, and Sheffield, UK: Equinox, 2016.

Ermi, Laura, and Frans Mäyrä. “Fundamental Components of the Gameplay Experience: Analysing Immersion.” Proceedings of DiGRA 2005 Conference: Changing Views – Worlds in Play, 2005. https://homepages.tuni.fi/frans.mayra/gameplay_experience.pdf.

Fritsch, Melanie, and Tim Summers. “Introduction to Part II: Creating and Programming Game Music.” In The Cambridge Companion to Game Music, edited by Melanie Fritsch and Tim Summers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. 59–63.

Giacosa, Gabriele. “Musical Meaning and the Semiotic Hierarchy: Towards a Cognitive Semiotics of Music.” Public Journal of Semiotics 10, no. 2 (2023): 16–39.

Grau, Oliver. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Translated by Gloria Custance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

Hart, Iain. “Semiotics in Game Music.” In The Cambridge Companion to Video Game Music, edited by Melanie Fritsch and Tim Summers, 220–37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Hocking, Clint. “Ludonarrative Dissonance in Bioshock: The Problem of What the Game is About.” Click Nothing (blog). October 7, 2007. https://clicknothing.typepad.com/click_nothing/2007/10/ludonarrative-d.html.

Hoggan, Eve, and Stephen Brewster. “Nonspeech Auditory and Crossmodal Output.” In The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook: Fundamentals, Evolving Technologies, and Emerging Applications, 3rd ed., edited by Julie A. Jacko, 211–35. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2012.

Huiberts, Sander. “Captivating Sound: The Role of Audio for Immersion in Computer Games.” PhD dissertation, Utrecht School of the Arts and University of Portsmouth, 2010.

Iwata, Satoru. Ask Iwata: Words of Wisdom from Nintendo's Legendary CEO. Edited by Hobonichi. Translated by Sam Bett. San Francisco: Viz Media, 2021. EPUB.

Kamp, Michiel. “Autoethnography, Phenomenology, and Hermeneutics.” In The Cambridge Companion to Video Game Music, edited by Melanie Fritsch and Tim Summers, 159–75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

———. Four Ways of Hearing Video Game Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024.

Margulis, Elizabeth Hellmuth. “Surprise and Listening Ahead: Analytic Engagements with Musical Tendencies.” Music Theory Spectrum 29, no. 2 (2007): 197–217.

Medina-Gray, Elizabeth. “Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music.” Music Theory Online 25, no. 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.25.3.2.

———. “Meaningful Modular Combinations.” In Music in Video Games: Studying Play, edited by K.J. Donnelly, William Gibbons, and Neil Lerner, 104–21. New York and Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2014.

Monelle, Raymond. The Sense of Music: Semiotic Essays. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Moseley, Roger, and Aya Saiki. “Nintendo’s Art of Musical Play.” In Music in Video Games: Studying Play, edited by K.J. Donnelly, William Gibbons, and Neil Lerner, 51–76. New York and Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2014.

Nelson, Will. “Link’s Sword is Mightier than the Pen: Composing and Performing in the Super Mario and Legend of Zelda Series.” Venture: The University of Mississippi Undergraduate Research Journal 6 (2024): 108–124.

Newman, James. “Before Red Book. Early Video Game Music and Technology.” In The Cambridge Companion to Video Game Music, edited by Melanie Fritsch and Tim Summers, 12–31. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Nintendo of America. Super Nintendo Entertainment System Consumer Information & Precautions Booklet. Redmond, WA: Nintendo of America, 1992.

Plank, Dana. “Audio and the Experience of Gaming.” In The Cambridge Companion to Video Game Music, edited by Melanie Fritsch and Tim Summers, 284–301. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Shahmehri, Demetrius. “Eurydice Sings: Revoicing a Musical Myth in Hades.” Journal of Sound and Music in Games 6, no. 1 (2025): 66–82.

Slate, Chris. “Living Up to a Legend: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time 3D.” Nintendo Power, no. 268 (June 2011): 82–85.

Smith, Jennifer. “Vocal Disruptions in the Aural Game World: The Female Entertainer in The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, Transistor, and Divinity: Original Sin II.” The Soundtrack 11, no. 1 (2020), 75–97.

Summers, Tim. The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time: A Game Music Companion. Bristol, UK: Intellect Books, 2021.

———. Understanding Video Game Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

Whalen, Zach. “Play Along: An Approach to Videogame Music.” Game Studies 4, no. 1 (2004) https://www.gamestudies.org/0401/whalen/.

Ludography

Ape Inc. and HAL Laboratory. EarthBound. Super Nintendo Entertainment System. Emulated via Nintendo Switch Online. Music by Keiichi Suzuki and Hirokazu Tanaka. Sound direction by Hirokazu Tanaka. Nintendo, 1994.

Game Freak. Pokémon Black Version and Pokémon White Version. Nintendo DS. Music by Shota Kageyama, Go Ichinose, Hitomi Sato, Junichi Masuda, and Minako Adachi. Sound direction by Minako Adachi. Tokyo and Kyoto: The Pokémon Company and Nintendo, 2010.

Grezzo and Nintendo EAD. The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time 3D. Nintendo 3DS. Music by Koji Kondo, Mahito Yokota, and Takeshi Hama. Sound direction by Yoshitaka Fujita. Kyoto: Nintendo, 2011.

Nintendo R&D4. The Legend of Zelda. Family Computer and Nintendo Entertainment System. Emulated via Nintendo Switch Online. Music and sound direction by Koji Kondo. Kyoto: Nintendo, 1986.

———. Super Mario Bros. Family Computer and Nintendo Entertainment System. Emulated via Nintendo Switch Online. Music and sound direction by Koji Kondo. Kyoto: Nintendo, 1985.

Nintendo EAD. The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds. Nintendo 3DS. Music by Ryo Nagamatsu. Sound direction by Masato Mizuta. Kyoto: Nintendo, 2013.

———. The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time. Nintendo 64. Emulated via Nintendo Switch Online. Music and sound direction by Koji Kondo. Kyoto: Nintendo, 1998.

———. Wii Sports. Wii. Music and sound direction by Kazumi Totaka. Kyoto: Nintendo, 2006.

Nintendo EPD. The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Wii U and Nintendo Switch. Music by Manaka Kataoka, Yasuaki Iwata, and Hajime Wakai. Sound direction by Hajime Wakai. Kyoto: Nintendo, 2017.

———. Mario Kart World. Nintendo Switch 2. Music by Atsuko Asahi, Maasa Miyoshi, Takuhiro Honda, and Yutaro Takakuwa. Sound direction by Takahisa Yamamoto. Kyoto: Nintendo, 2025.

Supergiant Games. Hades. Windows, macOS, Nintendo Switch, and others. Music and sound direction by Darren Korb. San Francisco: Supergiant Games, 2020.

Traveller’s Tales. Lego Star Wars: The Complete Saga. Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, Wii, and Nintendo DS. Emulated via Xbox Series X/S. Original music by John Williams. Additional music and sound direction by Adam Hay and David Whittaker. San Francisco: LucasArts, 2007.

———. Lego Star Wars: The Skywalker Saga. Nintendo Switch, PlayStation 5, Xbox Series X/S, and others. Original music by John Williams. Additional music by Simon Withenshaw. Sound direction by Tessa Verplancke. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Games, 2022.

Eve Hoggan and Stephen Brewster, “Nonspeech Auditory and Crossmodal Output,” in The Human-Computer Interaction Handbook: Fundamentals, Evolving Technologies, and Emerging Applications, 3rd ed., ed. by Julie A. Jacko (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2012), 222. The term earcon is a portmanteau of ear and icon, drawing a parallel between visual icons (or “eye-cons,” interpreted by sight) and earcons (interpreted aurally).

I hesitate to use the term “real-world” here because computers are very much part of the real world, but it is the only way I currently know to distinguish between activity on a computer and activity apart from a computer.

Zach Whalen, “Play Along: An Approach to Videogame Music,” Game Studies 4, no. 1 (2004), under “Ancestral Forms,” pars. 4–9.

Ibid., under “Super Mario Brothers,” par. 2.

Ibid., under “The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time,” par. 5.

James Newman offers an in-depth exploration of music technology through the lens of video game hardware capabilities in “Before Red Book: Early Video Game Music and Technology,” in The Cambridge Companion to Video Game Music, ed. Melanie Fritsch and Tim Summers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 12–31. Notably, he describes how a shift away from sound chips allowed composers and developers more freedom to use pre-recorded music in games. He also notes, though, that it’s reductive to mark the emergence of streaming audio as a “delineation,” especially as consoles that streamed audio and those that produced sound via chips evolved colinearly. Advanced forms of audio production, Newman claims, are not necessarily improvements, but simply different ways of producing audio for games with their own aesthetic draws.

Whalen, “Play Along,” under “The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time,” par. 5.

Michiel Kamp, Four Ways of Hearing Video Game Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024), 150.

Laura Ermi and Frans Mäyrä, “Fundamentals Components of the Gameplay Experience: Analysing Immersion,” Proceedings of DiGRA 2005 Conference: Changing Views – Worlds in Play, 2005, 7–8.

Gordon Calleja, In-Game: From Immersion to Incorporation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 43–44.

Isabella van Elferen, “Analysing Game Musical Immersion: The ALI Model,” in Ludomusicology: Approaches to Video Game Music, eds. Michiel Kamp, Tim Summers, and Mark Sweeney (Bristol, CT, and Sheffield, UK: Equinox, 2016), 34–39.

Musical architecture is a term I came up with that describes the momentary makeup of any number of sonic modules in a game. See Will Nelson, “Link’s Sword is Mightier than the Pen: Composing and Performing in the Super Mario and Legend of Zelda Series,” Venture: The University of Mississippi Undergraduate Research Journal 6 (2024), 109. Terms like Karen Collins’s “dynamic audio” relate more to the whole of a game’s audio rather than the moment-by-moment architecture of a game’s dynamic audio. See Karen Collins, Game Sound: An Introduction to the History, Theory, and Practice of Video Game Music and Sound Design (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 4.

Melanie Fritsch and Tim Summers, “Introduction to Part II: Creating and Programming Game Music,” In The Cambridge Companion to Game Music, eds. Melanie Fritsch and Tim Summers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 62.

A newer entry in the Lego Star Wars series was released in 2022 to include the Sequel Trilogy of Star Wars series (2015–2019). Lego Star Wars: The Skywalker Saga is an open-world take on the series, and in copy and pasting side quests, feels a lot flatter of a gaming experience than The Complete Saga. For better or worse, though, there isn’t much noteworthy about its sound direction.

Elizabeth Medina-Gray, “Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music,” Music Theory Online 35, no. 3 (2019), pars. 11–12.

Kamp, Four Ways of Hearing Video Game Music, 168.

Nelson, “Link’s Sword is Mightier than the Pen,” 113–114.

It’s a bit problematic to be talking about sound chips when I’m emulating The Legend of Zelda on a system that streams audio. However, the emulator exhibits the exact behavior I describe, so even without an authentic NES experience, the Switch 2 emulation will do.

Nintendo EPD, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, Nintendo Switch (Kyoto: Nintendo, 2017), tip during a loading screen.

Clint Hocking, “Ludonarrative Dissonance: The Problem of What the Game is About,” Click Nothing (blog) (October 7, 2007), par. 4.

Demetrius Shahmehri, “Eurydice Sings: Revoicing a Musical Myth in Hades” Journal of Sound and Music in Games 6, no. 1 (2025), 69.

Three-dimensional on a two-dimensional screen, of course. Ocarina of Time is arguably four-dimensional since Link travels back-and-forth through time, but I digress.

Tim Summers, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time: A Game Music Companion (Bristol, UK: Intellect Books, 2021), under “Introduction,” 1.

Chris Slate, “Living Up to a Legend: The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time 3D,” Nintendo Power, no. 268 (June 2011), 85.

Nintendo EAD, The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds, Nintendo 3DS (Kyoto: Nintendo, 2013), message while saving the game at a wind vane.

Satoru Iwata, Ask Iwata: Words of Wisdom from Nintendo's Legendary CEO, ed. Hobonichi, trans. Sam Bett (San Francisco: Viz Media, 2021), under “EarthBound and Expanding The Gaming Population,” par. 8. EPUB.

Nintendo of America, Super Nintendo Entertainment System Consumer Information & Precautions Booklet (Redmond, WA: Nintendo of America, 1992), 1. Emphasis added.

Learned something new again! I’m glad that creators think through all aspects of video gaming!